In the beginning, there were institutions...thoughts on institutions, economics and other random topics.

Friday, August 7, 2009

Tyler Cowen on Progressivism

I'd suggest looking at all 11 points in favor of the idea, bearing in mind the second-to-last paragraph: "In due time I'll be writing more systematically about why those views are not, on the whole, my own. But not today!" I particularly like #6 and #8.

Dr. Cowen is generally a skeptic of government interventions, so it will be interesting to see his critiques.

6. Limiting inequality will do more to check bad governance than will the quixotic libertarian attempt to limit the size of government.

8. We should support free trade, more immigration, and more foreign aid, but the nation-state will remain the fundamental locus for redistribution. That means helping the poor at home more than abroad; a decision to do otherwise would destroy political equilibrium and make everyone worse off.

Dr. Cowen is generally a skeptic of government interventions, so it will be interesting to see his critiques.

Mark Thoma on Economic Models

A map has always been a principles-level analogy for why models are useful. Mark Thoma gives us a nice twist on it:

But all the tools in the world are useless if we lack the imagination needed to build the right models. Models are built to answer specific questions. When a theorist builds a model, it is an attempt to highlight the features of the world the theorist believes are the most important for the question at hand. For example, a map is a model of the real world, and sometimes I want a road map to help me find my way to my destination, but other times I might need a map showing crop production, or a map showing underground pipes and electrical lines. It all depends on the question I want to answer. If we try to make one map that answers every possible question we could ever ask of maps, it would be so cluttered with detail it would be useless, so we necessarily abstract from real world detail in order to highlight the essential elements needed to answer the question we have posed. The same is true for macroeconomic models.I may have to use that in class.

Tuesday, August 4, 2009

Worth Sharing

More dumb quotes, in case Art Laffer's credibility hadn't fully depreciated.

1. I've never had a problem with the Post Office.

2. The DMV is run by the states not the federal government.

3. Medicare and medicaid are the health care of almost 20% of all americans is already done by the government

If you like the Post Office and the Department of Motor Vehicles and you

think they’re run well, just wait till you see Medicare, Medicaid and health

care done by the government.

- "Economist" Arthur Laffer during an appearance on CNN.

1. I've never had a problem with the Post Office.

2. The DMV is run by the states not the federal government.

3. Medicare and medicaid are the health care of almost 20% of all americans is already done by the government

Relating things back to Trade and FDI

I wonder if anyone has estimated the number of jobs offshored due to the fact that health insurance here is employer-paid, and not publicly-paid, like it is in other countries. How much would it decrease the total benefits employers would be paying if the current mandates were dropped?

4.9%

That is the percentage of the market presumably covered by individual non-employer, non-public health insurance in 2007, according to the CDC. In my view, these are the only folks who would lose their "choice" over health care, unless you count the 16.6 percent who have no insurance. I suspect that the "majority" of Americans who are happy with their insurance are either (a) in a public option already (medicare, medicaid, VA/Tricare/military); or (b) in an employer-provided plan, over which they have no choice, but are probably getting a good deal on, on average (because of independent selection into the pool). Has anyone polled just insurees who purchase insurance on the private market (or those who are uninsured)? I'd be curious to see how the "choosers" feel about public option.

More on Stupid Meetings

From Reuters' Felix Salmon. My quote of the day:

In a badly-managed business, you get massively-multiplying meetings: every

decision, no matter how tiny, ends up being debated and signed off on

by far too many people, who thereby get to feel (and show their bosses)

that they’re Doing Something.

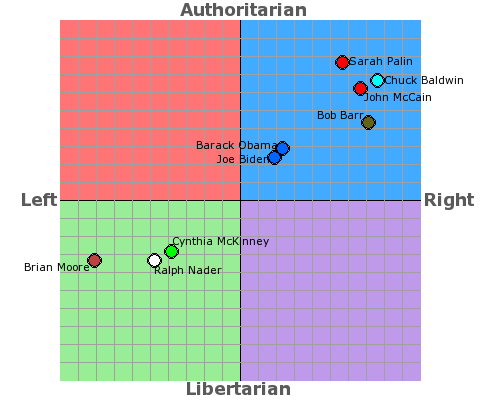

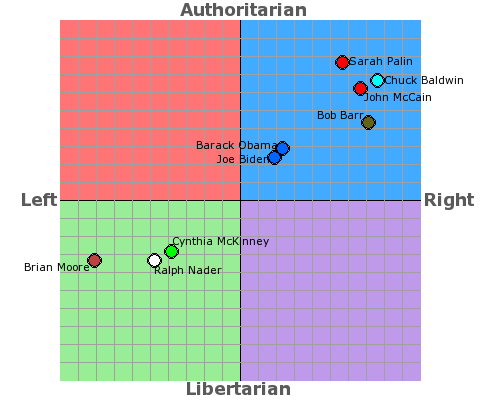

More on the Political Compass

One of the problems with survey data (especially the Likert-scale type of survey represented in the Political Compass) is that magnitudes are almost meaningless. Statistically, in order for me to compare, say, my dad, with, say, John McCain or Barack Obama it has to be the case that: (1) both of those figures took the test (they didn't); and (2) the magnitudes on the scale are meaningful (they're not).

Economically, putting magnitudes on preferences (cardinal utility) is something that has been recognized as fruitless for some time, although political scientists and psychologists still try to do so. This leads to the crux of the various "impossibility theorems" in the various critiques of the notion of "social welfare" in economics.

Inter-personal comparisons of "utility" or magnitudes of preference in a survey like the Compass requires me to assume that both people know what is meant by "Agree" as opposed to "Strongly Agree" in the Likert Scale, that they agree on that meaning, and so on. Usually, people don't agree on the intensity meant by "Strongly" in these surveys and the study faces the problem of not having "Inter-Rater Reliability." For a statement like, "If economic globalisation is inevitable, it should primarily serve humanity rather than the interests of trans-national corporations," it can be hard to have strong feelings for or against because "serve humanity" can mean different things to different people. Also, are the interests of "humanity" and "corporations" necessarily conflicting? I put "agree" on this because I think that freer trade and factor movements do serve humanity even if they serve corporations in the process. How intensely to I believe this? I guess pretty strongly, but the loadedness of the question makes me tentative.

My suggestion for the authors would be to make the survey binary - "agree" or "disagree." That way, their index would map to a well-defined and well-calibrated as a ratio-scale varilable. The current scale for the responses maps to a poorly calibrated interval-scale variable (and probably give a better dispersion of views for comparisons. Here are some pictures of their comparisons of various leaders:

Leaders:

2008 US Presidential Candidates:

2008 US Presidential Candidates:

2004 Presidential Candidates:

2004 Presidential Candidates:

UK Political Parties (Current and Over time):

UK Political Parties (Current and Over time):

Economically, putting magnitudes on preferences (cardinal utility) is something that has been recognized as fruitless for some time, although political scientists and psychologists still try to do so. This leads to the crux of the various "impossibility theorems" in the various critiques of the notion of "social welfare" in economics.

Inter-personal comparisons of "utility" or magnitudes of preference in a survey like the Compass requires me to assume that both people know what is meant by "Agree" as opposed to "Strongly Agree" in the Likert Scale, that they agree on that meaning, and so on. Usually, people don't agree on the intensity meant by "Strongly" in these surveys and the study faces the problem of not having "Inter-Rater Reliability." For a statement like, "If economic globalisation is inevitable, it should primarily serve humanity rather than the interests of trans-national corporations," it can be hard to have strong feelings for or against because "serve humanity" can mean different things to different people. Also, are the interests of "humanity" and "corporations" necessarily conflicting? I put "agree" on this because I think that freer trade and factor movements do serve humanity even if they serve corporations in the process. How intensely to I believe this? I guess pretty strongly, but the loadedness of the question makes me tentative.

My suggestion for the authors would be to make the survey binary - "agree" or "disagree." That way, their index would map to a well-defined and well-calibrated as a ratio-scale varilable. The current scale for the responses maps to a poorly calibrated interval-scale variable (and probably give a better dispersion of views for comparisons. Here are some pictures of their comparisons of various leaders:

Leaders:

2008 US Presidential Candidates:

2008 US Presidential Candidates: 2004 Presidential Candidates:

2004 Presidential Candidates:  UK Political Parties (Current and Over time):

UK Political Parties (Current and Over time):

Monday, August 3, 2009

Welfare and Liberty

I was talking about the Arrow "impossibility theorem" with a friend the other day, and was reminded of a paper by Amartya Sen (1976, Economica) that proves an application of the result. It basically goes like this: The principle of Pareto Efficiency (Optimality, that if everyone is at least as well-off under a certain policy than the status quo it should be pursued) is not completely compatible with personal liberty (that each person should be free to choose for themselves). In other words, he proves "the impossibility of the Paretian Liberal" (liberal in the classical sense, i.e. "libertarian"). The crux of it is that you can ideologically favor liberalism, but in certain circumstances this will lead to a loss in welfare, or utility for certain individuals. Politically, any party will argue for either side, depending on how it suits their perceived constituencies or predetermined preferences.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)